After determining the data sources during the product planning phase of the project (discussed in my previous post), it was time to move into the data engineering phase. The primary goal was to integrate two datasets: the real energy usage for two months and the corresponding weather data, along with the weather data for the rest of the year. This combined dataset would serve as the foundation for the regression model used to predict future energy consumption.

Initial Approach to Web Scraping

At first, I thought the web scraping portion would be straightforward. My plan was to simply:

- Use the requests library in Python to fetch the HTML source code of the weather data website.

- Parse the HTML response using Beautiful Soup, and extract the relevant table elements containing the weather data.

- Repeat this process for every day within the user-defined date range to build a complete dataset.

The Problem: Dynamic Content

However, when I ran the code, I realized there was a significant issue. The weather data I was after wasn’t included in the initial HTML response. The table containing the weather data was being loaded dynamically via JavaScript after the page had already loaded.

This was an unexpected challenge. Simply fetching the initial HTML was not going to be enough. I needed to capture the fully rendered page, including the JavaScript-executed content.

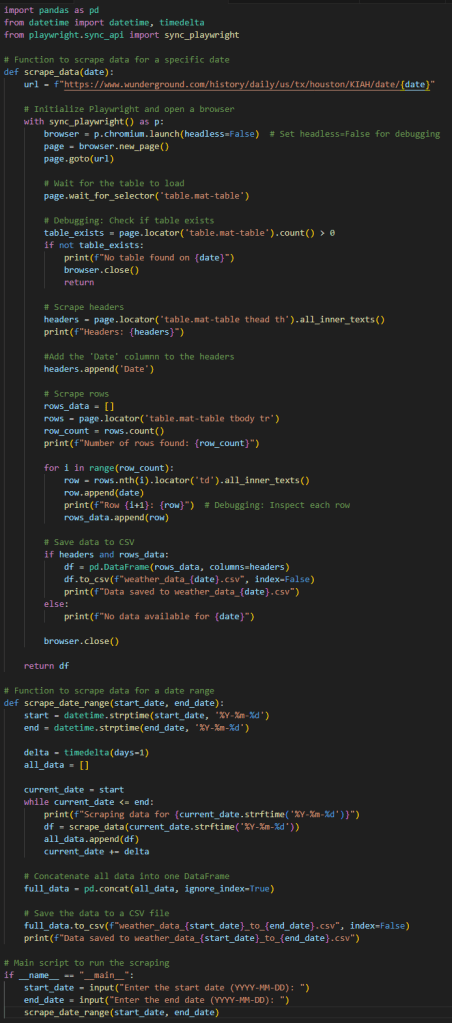

Here’s the initial Python code I I committed to github for this task that accounted for the dynamic content:

Proxy Management for Scaling Web Scraping

As the project progressed, I encountered another unexpected roadblock—an HTTP 400 error. At first, there wasn’t much detail about the issue, but after exploring the problem, I learned that it was caused by rate limiting. This was because I was pinging the website too frequently.

The nature of the website’s dynamic JavaScript content meant that I wasn’t simply requesting data once per page load. Instead, I was sending multiple requests to retrieve various parts of the webpage’s content. Each time I requested the weather data, I had to make multiple requests per day, amounting to five requests per webpage. Multiply that by 365 days (to collect hourly weather data for a full year), and I was sending over 1,500 requests in a short amount of time.

This kind of traffic from a single IP is easily identifiable by website security systems as bot activity, which resulted in my IP being blacklisted. Essentially, I could no longer access their website from any device connected to my home WiFi network.

Solving the Rate Limiting Issue: Proxy Management

After some research, I came across the concept of proxy management, which is commonly used to circumvent issues like rate limiting in web scraping.

Proxy management allows web scrapers to route their requests through a pool of proxy servers, distributing traffic across multiple IP addresses rather than sending all requests from a single IP. This helps avoid triggering rate limits or being identified as bot traffic. It can also be used to bypass geographical restrictions, access blocked content, or scrape at a larger scale.

Some of the common use cases for proxy management in web scraping include:

- Avoiding rate limits: When websites restrict the number of requests from a single IP within a given time frame, proxies help distribute requests to prevent this.

- Masking IP identity: Proxies allow scrapers to change IP addresses, making it harder for websites to block traffic from a single IP.

- Scaling data scraping: For projects requiring data collection from a large number of pages, proxies are essential for scaling the operation efficiently.

The Solution: Using ScrapingBee

After evaluating several proxy management solutions, I opted for ScrapingBee (link here), which offered an easy-to-integrate API. Given the relatively small size of my project, I enrolled in their free plan, which was more than sufficient for my needs.

Once I incorporated ScrapingBee’s API into my web scraping code, it worked seamlessly. The proxy management allowed me to distribute my requests across multiple IP addresses, resolving the rate-limiting issue and allowing me to continue scraping the weather data I needed.

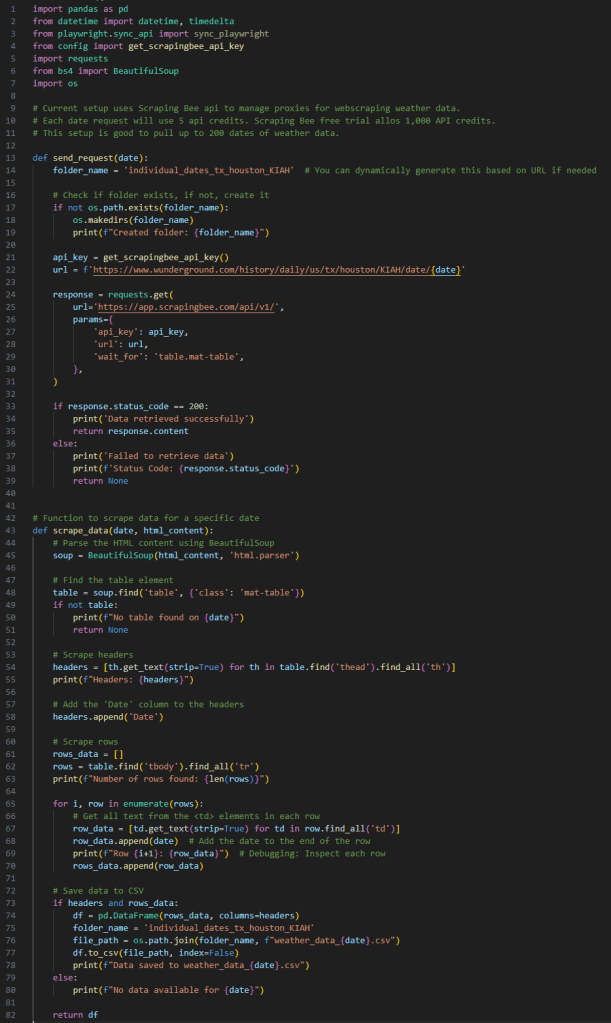

Here’s how I adjusted my code to integrate ScrapingBee’s proxy management:

By using ScrapingBee, I was able to continue my data collection process without interruption, ensuring that I had all the necessary data to feed into my energy usage prediction model.

Payloads and Data Storage

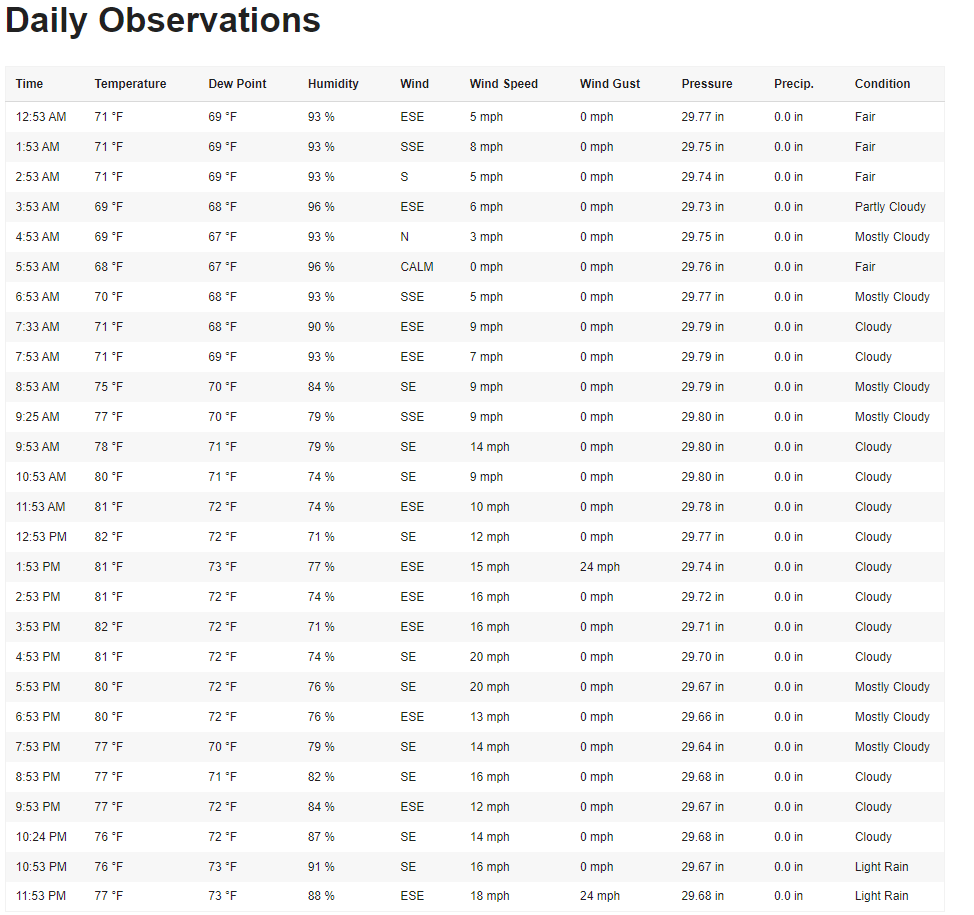

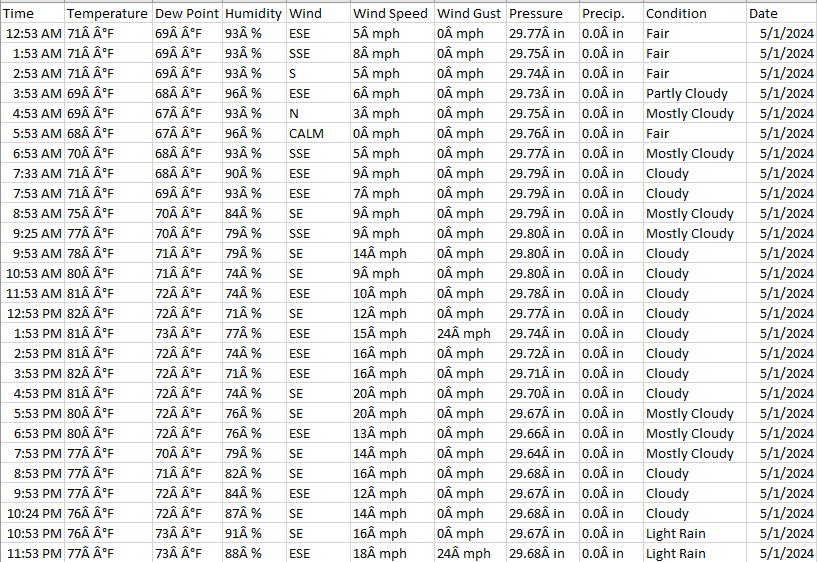

The end result of these web scraping efforts were converting payloads of table data formatted from this:

To this:

If you take a closer look at the code, you’ll notice that I saved the tables as individual CSV files in my project directory. This approach stems from my experience working with contact center API JSON payloads from a SaaS vendor during my time at a healthcare practice. I found that keeping the web scraper as a modular component of the ETL process is crucial, as it prevents the scraper from directly loading data into the SQL database.

This separation not only makes the process more flexible but also allows for future enhancements. For instance, I could easily drop these individual CSV files into a cloud directory, enabling a triggered event to grab the new data and load it into the database as a secondary component of the ETL pipeline. This kind of modularity ensures that the web scraping process can be adapted and expanded as needed, depending on the data team’s SOP (Standard Operating Procedure) for ETL pipelines.

Typically, it’s best to avoid a monolithic architecture where the entire codebase is tied to a specific product like PostgreSQL, Google Cloud Platform, or similar technologies. Instead, building components with modularity in mind provides flexibility and scalability, ensuring that the solution can evolve without being dependent on any one product or service.

If you’re interested in learning more about this concept, feel free to drop a comment below. I’d love to discuss it further!

Loading Data into the SQL Database

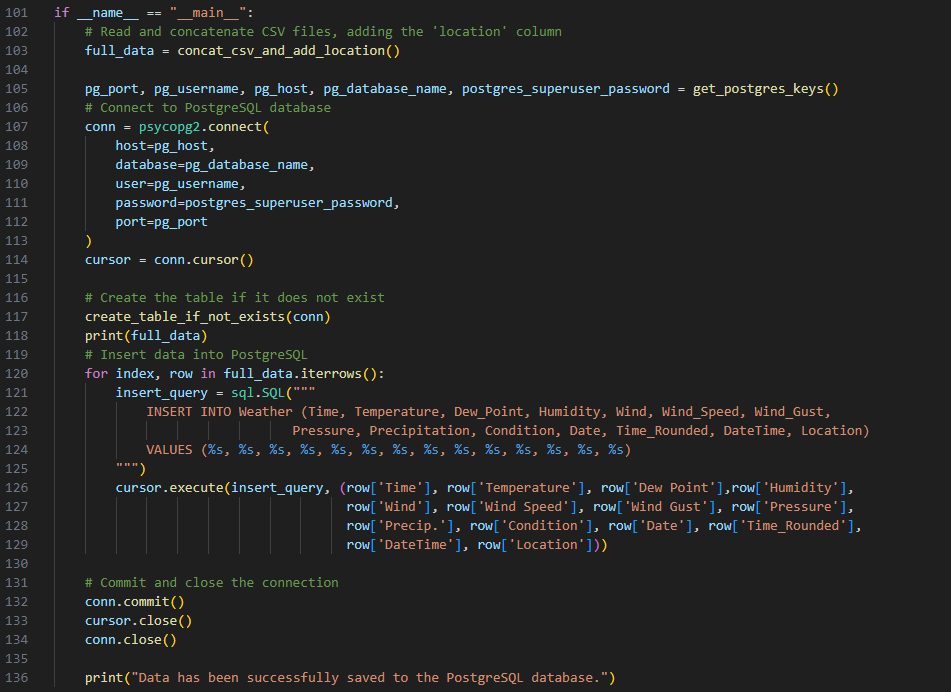

Once the web scraping process was completed, the next task was to load the scraped weather data into the SQL database. This was done using libraries like SQLAlchemy and psycopg2. Here is the code that was used:

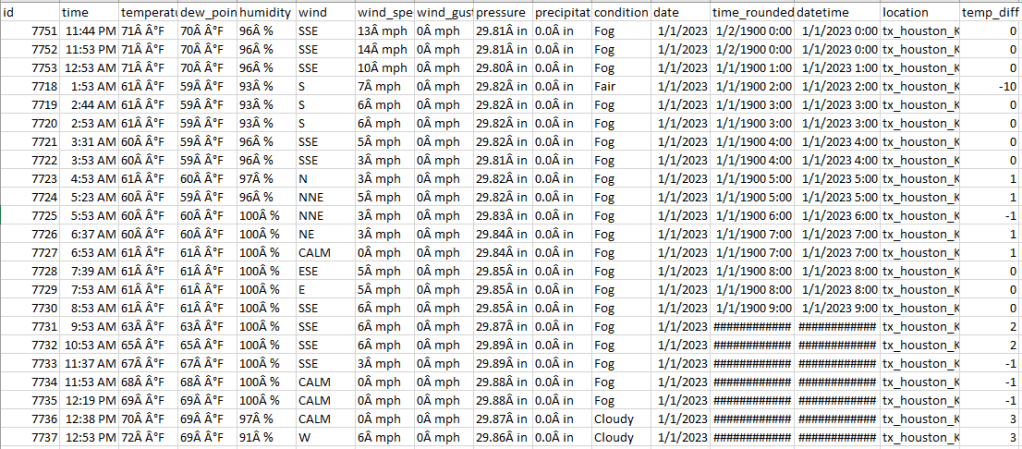

Here is the resulting postgreSQL table:

With that portion of the data gathering done, it was time for the data science team to get their hands dirty with the combined weather and real energy usage data, designing the regression model that would predict energy usage based on weather seasonality.

Final Dataset and Next Steps

The next step involved cleaning, preprocessing, and merging these datasets into a final form for model training. This final dataset combined two months’ worth of real energy usage data, the correlating weather data, and the remainder of the year’s weather data. With the data now fully prepared, the data science team could move on to building the model, which would predict energy usage for the year based on weather trends and patterns.

In my next blog post, I’ll discuss the intricacies of model building, focusing on how the regression analysis was used to predict future energy usage based on seasonal weather patterns.

Leave a comment